Hans van Lemmen | Historical Tiles writing about tiles and architectural ceramics

BRIEF HISTORY OF TILES

The making and decorating of tiles has gone on for thousands of years and in many ways the history of tiles is a reflection of the entire history of cultural endeavour. They were used to protect and decorate the walls of some of the earliest buildings in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt and are still used today on an unprecedented scale in every form of architecture for their functional and decorative qualities. Tiles come in many shapes and forms and if the word is not used too restrictively it can also be stretched to cover bricks and architectural terracotta and faience. The Romans gave us the word ‘tile’ from the Latin word tegula which in Roman times meant terracotta roof tiles. Tiles can be unglazed or glazed, have moulded, painted or printed decorations, but whatever their shapes, ornamentation or applications, tiles are valued above all for their permanence and durability. Wood rots, stone wears away and metal corrodes, but a well-made and properly fired tile will last almost for ever.

Tiles are in the first instance a functional building material and are used to protect buildings from the weather, or are applied in interiors to make floors, walls and sometimes even ceilings, more fireproof, hygienic and easier to clean. They have also from the very beginning been valued for their decorative and ornamental qualities, and because in the early days tiles and bricks were an expensive commodity, they came to symbolize the power and prestige of the rulers who commissioned them. Blue faience tiles lined the underground corridors of the Step Pyramid (2686-2613 BC) of Pharaoh Djoser in Saqqara in Egypt and ornamental glazed bricks with bulls and dragons covered the walls and towers of the Ishtar Gate (605-562 BC) of the city of Babylon in Mesopotamia built on the orders of Neo-Babylonian ruler Nebuchadnezzar II. From the 6th century BC onwards, the Greeks, Etruscans and Romans used decorative terra roof tiles with great effect on their temples. The Chinese applied coloured glazes to their roof tiles and shaped them in the form of fantastic beasts like dragons to ward off evil.

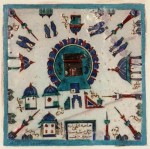

Wall tiles became an important form of decoration for the first time from the ninth century AD onwards in countries where Islamic culture predominated. Islamic potters pioneered the making of lustre tiles for use in mosques, palaces and holy shrines. Lustre decorations were created by combining metal compounds of silver or copper with the glaze producing a thin film of metal on the surface of the fired tile that reflected light and these tiles are still regarded as some of the most beautiful ever produced. Islamic potters also pioneered other ceramic techniques such as cuerda seca, tile mosaic and under glaze painting. The latter in particular flourished with astonishing results in the Ottoman Empire during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when the Turkish town of Iznik became an important centre of pottery and tile production. Colourful under-glaze painted tiles with exquisite floral decorations were produced for use in the palaces and mosques of the ruling elite in Istanbul.

In northern Europe the first tiles were made during the Middle Ages. During the thirteenth century magnificent mosaic floors made of lead-gazed tiles were laid in the abbey churches of Fountains, Byland and Rievaulx in North Yorkshire, and monastic establishments throughout northern Europe were important patrons of this type of floor tile. The greatest innovation in medieval tile making was the production of so-called ‘two-colour’ tiles that consisted of inserting white coloured clay into the red clay of the tile body. After glazing, the white clay became yellow and the red clay turned a deep red-brown. Such tiles were decorated with a range of simplified floral patterns, figurative designs and religious images and were used to create stunning floors in churches, royal palaces and in the houses of the well-to-do. The mid-thirteenth century floors excavated at Clarendon Palace in Wiltshire and Chertsey Abbey in Surrey (now in the British Museum) are celebrated cases in point.

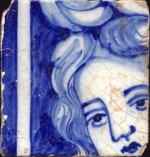

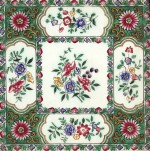

The real glory in European tile making came with the production of tin-glazed tiles (known as ‘maiolica’ in Italy and as ‘delftware’ in Holland and England). It was a technique initially developed by the Islamic potters in the Middle East which spread first to southern Europe and then north. Clay tiles were covered with a white glaze made from lead oxide to which tin oxide had been added. This turned the original transparent lead glaze into an opaque white glaze, and in a sense tiles became small white ‘canvases’ on which all manner of designs and figurative subjects could be painted in vivid colours like blue, green, orange and purple. In fifteenth and sixteenth century Italy such tiles were made mainly for use on the floors of churches and in the palaces of the ruling classes but in seventeenth century Holland they were used to cover the walls of the houses of middle class burghers and from that time tiles were commonly found in many homes.

Until the middle of the eighteenth century tiles had been made and decorated by hand but the emergence of the Industrial Revolution in Britain had a great impact on the manufacturing and decoration of tiles. In 1756 the printer John Sadler in Liverpool applied transfer printed images taken from engraved woodblocks to the surfaces of glazed tiles, and went on to transfer images taken from engraved copper plates. This was the beginning of transfer printing on tiles which became a common technique in the nineteenth century.

In 1840 the Birmingham engineer Richard Prosser invented a process whereby he could compress finely powdered clay under great pressure in a screw press. The Stoke-upon-Trent ceramics manufacturer Herbert Minton bought a stake in this revolutionary invention of dust pressing clay and adapted it to make machine pressed tiles thereby bringing about the mass production of tiles. The price of tiles fell and this, combined with quicker decoration methods like transfer printing meant that tiles were now readily available and could be used on a large scale in public buildings and homes. Special handmade and hand painted tiles were still produced however particularly by adherents of the Arts and Crafts Movement like William Morris and William De Morgan who refused to accept machine production and catered for exclusive markets.

In the twentieth century tiles were also strongly influenced by the major style phenomena like Art Nouveau and Art Deco and between 1900 and 1940 the market was flooded with brightly coloured tiles in those two popular styles which have now become coveted collectors’ items. Tiles are still very much with us now as mass produced items for use in architectural settings or as special products made by tile artists for specially commissioned locations. Underground stations for example often have tile installations to give character to their interiors. Modern artists also design and make tiles as objets d’art. Tiles provide them with plasticity, ceramic pigments and colourful glazes to work with that are transformed by fire into something very durable unobtainable in other media.

The colourful story of decorative tiles from ancient beginnings to the present day is told in detail in 5000 Years of Tiles published by the British Museum Press, 2013. It is richly illustrated with tile art from the British Museum and other museums in Europe and America.

- Egyptian wall tile, 2686-2613 BC.

- Assyrian glazed bricks, 883-859 BC.

- Roman terracotta roof tile (tegula) c. 50 BC.

- English medieval floor tiles c. 1250

- Turkish painted wall tile showing a stylised image of the Ka’ba in Mecca c. 1650

- Italian maiolica floor tiles, early 16th century

- Dutch delftware tile, early 17th century

- Portuguese tin-glazed wall tile, 1750-1800

- English delftware tile c. 1750

- English transfer-printed tile, 1777-80

- English transfer-printed tile 1835-40

- English dust-pressed tile c.1895

- English Art Nouveau tiles c. 1900

- English Art Deco tile, c. 1935

- English screen-printed tile by Peggy Angus c.1952